Opinion

Compulsory voting is not the answer Nigeria beeds right now, by Ezenwa Nwagwu

The House of Representatives recently made headlines with a proposed legislation that could criminalize non-voting in Nigeria. Surprisingly, the Bill was sponsored by the Speaker of the House, Rt. Hon. Abbas Tajudeen.

Since the news broke, it has stirred intense debate across the country, with many Nigerians questioning its fairness.

On the surface, the bill sounds like a sincere attempt to revive civic responsibility in a country grappling with low voter turnout. But in reality, it raises a far more troubling question: when did participation in democracy become something to be enforced by law rather than inspired by trust?

However, I believe the buzz being generated over the proposed bill provides an opportunity: not just to reject coercion, but to reflect on better, more sustainable ways to build trust in the electoral process and strengthen our democracy.

My aim in this discussion therefore, is to offer alternatives and help spark a more robust, constructive conversation about how to genuinely improve citizen engagement, not through compulsion, but through advocacy that builds trust in the system.

Let me begin by saying that I believe that the intention behind the bill may be noble, but its premise is fundamentally flawed. Yes, in theory, higher turnout makes for a healthier democracy, but you can not improve participation by threats. Low turnout isn’t just a sign of apathy. It’s a symptom of a deeper crisis of faith in our democracy that must be corrected through various approaches, which we will address here.

Instead of criminalization, what we need is advocacy, targeted, sustained, and people-focused. Citizens must come to understand that the cost of bread, electricity, hospital bills, all of it is tied to the leaders we elect, and by extension, to the votes we cast.

That is the kind of civic awareness that leads to meaningful participation. But this requires more than token campaigns every four years. It calls for deliberate investment in civic education, not just by INEC or the National Orientation Agency, but across all layers of government and civil society.

In Ghana, for instance, civic educators are employed year-round to go door-to-door, engaging citizens in plain language about their rights and responsibilities. That is what commitment to voter engagement looks like. In Nigeria, however, our default response to every national challenge is to throw a law at it. But how many of our existing laws have truly fixed the problems they were meant to solve? If we’re serious about democracy, then we must resist the urge to legislate apathy away. Instead, we must invest in increasing public trust, one voter at a time.

Secondly, let me say that the proposed legislation feels more like a distraction from the deeper issues plaguing Nigeria’s electoral system. It reflects a misplaced legislative priority at a time when the country grapples with more urgent democratic challenges.

It is my opinion that instead of mandating voting through threats of legal penalties, lawmakers should instead be focusing on removing the systemic barriers that discourage citizens from participating in elections in the first place.

Forcing citizens to vote without fixing the very system that is driving them away risks not only deepening resentment but undermining the democratic values we claim to defend. If lawmakers truly want to strengthen democracy, there are far more urgent bills begging for attention.

For instance, one of the most critical and long-overdue reforms that the National Assembly should prioritize is the passage of the Electoral Offenses Commission Bill. This bill, which has languished in legislative limbo for years, seeks to establish an independent body to investigate and prosecute electoral offenders.

The question is ,why has this bill taken so long to pass? Its enactment would demonstrate real commitment to electoral integrity by deterring malpractice and ensuring consequences for those who subvert the will of the people. Strengthening enforcement mechanisms around elections will naturally build trust and encourage voluntary participation.

Another legislative proposal that, in my opinion, deserves far more attention than the compulsory voting bill is a quiet but impactful amendment to the Electoral Act, 2022, one that seeks to eliminate by-elections, a system which puts a lot of financial and logistical burden on Nigeria’s democracy.

Under current law, any vacancy in the legislature caused by death, resignation, or incapacitation must be filled through a fresh by-election. In most cases, what we see is that this system is flawed. For instance, when a Senator dies, in most cases, it is the House of Representatives member from that Constituency that contests and wins the election. While the Reps member moves to the Senate, his seat becomes vacant, which gives room for another by-election to fill his position.

However, the legalisation proposed by Hon. Adebayo Balogun proposes a smarter route: allow political parties to nominate a replacement within 60 days, subject to ratification by INEC. No ballot boxes. No unnecessary budgets. No wasted logistics.

To appreciate the impact, consider the economics. By-elections for senatorial seats cost billions. The financial cost for three senatorial by-elections could equal the cost of one full governorship election. Imagine the waste of resources if INEC has to conduct by-elections in two senatorial districts—while also preparing for more general or off-cycle polls. This bill could plug this fiscal leak, allowing funds to be better spent on voter education, electoral infrastructure, or civic engagement initiatives.

But beyond cost, the proposal introduces a more efficient process. Once a party nominates a replacement and INEC ratifies it, the new legislator is sworn in—ensuring continuity in governance without the long interregnums that currently follow legislative vacancies.

Countries like the UK have informal versions of this, with parties often retaining seats through loyalist nominations in by-elections. Germany goes further, using a party list system that automatically fills legislative vacancies without public voting.

Of course, this reform is not without legal concerns. Critics might argue it undermines direct representation—a foundational principle of democracy. That’s a valid caution. To avoid democratic backsliding, the nomination process must be transparent, inclusive, and merit-based—not merely a reward for party loyalists. INEC’s role in ratifying nominees becomes even more critical, ensuring replacements reflect the public interest, not just political expediency.

Still, as Nigeria navigates a tight fiscal space and a fragile democracy, this is the kind of reform that reflects serious thinking. It tackles real-world inefficiencies without eroding fundamental rights, and that’s far more than can be said for a bill that seeks to jail people for not voting. If the National Assembly is truly interested in strengthening our democracy, it should focus on such smart, constructive legislation.

In the end, the National Assembly must ask itself what kind of democracy it wants to build. One that compels citizens to vote under threat of punishment? Or one that creates an efficient, transparent system people actually believe in.

Nwagwu is the Executive Director Peering Advocacy and Advancement Centre in Africa (PAACA)

-

Crime and Law1 day ago

Crime and Law1 day agoImo community decries killings, seeks urgent government action

-

Sports1 day ago

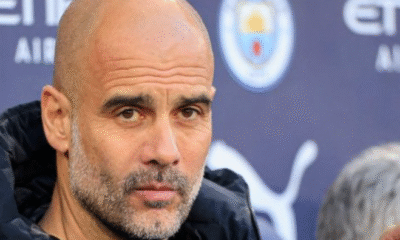

Sports1 day agoPep Guardiola speaks on Manchester City Champions League qualification

-

Politics1 day ago

Politics1 day agoAbia: Why Tinubu should shun Alex Otti’s invitation to commission one project – Orji

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoAncelotti’s possible Brazil squad leaked

-

Metro News2 days ago

Metro News2 days agoBreaking: Many feared dead in tragic accident on Karu Bridge

-

Metro News2 days ago

Metro News2 days agoPeter Obi gifts N20m to Abuja Anglican hospital, school projects

-

Crime and Law1 day ago

Crime and Law1 day agoTerrorists storm church, kidnap female worshippers in Kebbi

-

Metro News1 day ago

Metro News1 day agoMassive protest begins in Ibadan over police stray bullet killing WAEC candidate